The Dead

& Ulysses in 80 Days

In late May, my family went to Ireland for 10 days. We picked it because it was a place none of us had been to, and all of us had expressed a desire to visit. We all fell in love with Ireland in ways we hadn’t fully anticipated: for its wondrous natural beauty; for the daily music (trad!); for the kind and friendly people we encountered everywhere we went; and finally, especially in Dublin, for a place that exudes a love of literature like I have rarely felt elsewhere. There was the unbidden joy of surprisingly being asked to read a page of Finnegan’s Wake aloud in Sweny’s Pharmacy where Ulysses’ Bloom famously bought lemon soap for his wife, Molly (yes, we bought some too), with my kids and husband staring through the window wondering what on earth I was doing in there; and the thrill of being told that books in Ireland are not taxed, which for some reason convinced me and the girls that it was a necessity that we stock up on books in Ireland (in English) that were of course available in Canada and the US, but still…!

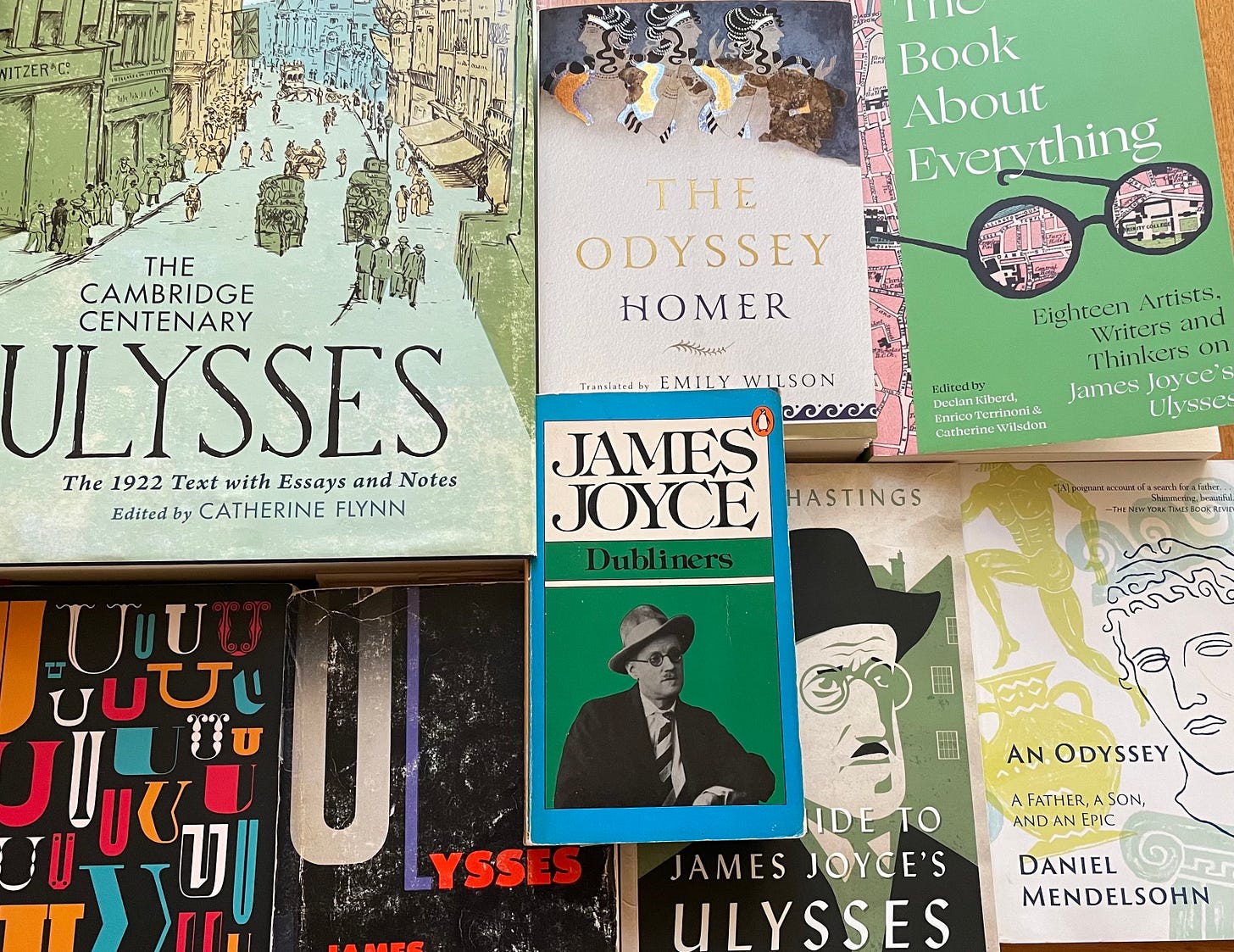

Just before we left, Ariel and I found out about Ulysses in 80 days, an international reading group that followed daily reading prompts on Twitter, FB, or email with the starting and end point for each day. Due to this year being the centenary of the publication of Joyce’s Ulysses, you can imagine the number of collections published celebrating the genius of Joyce and this masterpiece. I had read it (sort of) over 35 years ago in an English class at Columbia University that devoted a full semester to this novel. I readily admit that I retained almost nothing from this course, other than a love for the last thirty pages, the so-called Penelope section, with Molly’s famous stream of conscious monologue, and yes, yes, yes. Ariel listened to Ulysses predominantly on audio (see RTE’s wonderful production here); I sometimes tuned into that, but mostly read it switching between my old college copy and the gigantic Cambridge Centenary edition with the 1922 text with essays and notes. In addition, I turned to Patrick Hasting’s The Guide to James Joyce’s Ulysses (great online and in hard copy); to essays in The Book About Everything: Eighteen Artists, Writers and Thinkers on Jame’s Joyce’s Ulysses; and essays by Daniel Mulhall, Ireland’s Ambassador to the US, Ulysses: A Reader’s Odyssey. Alongside those, having forgotten all the ties between Ulysses and The Odyssey, I decided it was high time to re-read The Odyssey (or to be honest, to read it in full for the first time), and for that I turned to translations by Robert Fagles, and my favorite one by Emily Wilson. My dad reminded me that Daniel Mendelsohn, whose memoir The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million, that I had loved, had also written a memoir about teaching The Odyssey at Bard College, and having his 82-year-old dad sit in on the class. I highly recommend that book as well: A Father, A Son, and an Epic. It is quite a beautiful tribute to his father, as well as an eye-opener into The Odyssey. It has been a summer of a lot of self-learning, and when I do it well and deliberately, it is enriching in ways that are hard for me to express. In short, it gives my life more meaning.

I’ve been reading aloud to my friend Bill for many years now — we think it is probably close to 15. As I mentioned in this newsletter once before, I went to him seeking advice on the wisdom of donating a kidney (per the request of my husband). Bill practiced medicine for many years in Boulder, and was beloved by his patients. Very unfortunately, during a surgery for his back, he ended up going blind. Over and over again through the years, even though he doesn’t practice anymore, he has given me and Chris sound medical advice. So when I went to talk to him about giving a kidney, (in another search to give my life more meaning), he suggested reading to a blind man instead. I took him up on his offer, and it has been a high point of my week (and I hope his) for many years. These last couple weeks, continuing my love of all things Irish, we read a short story by Edna O’Brien, and Joyce’s “The Dead,” which took us two sessions. I’ve read “The Dead” a couple times before, and have always responded to it, but this time was entirely different, likely because I have been so subsumed in reading Joyce and about Joyce, and probably also because of where I am now at 55: with older parents (my dad celebrated his 91st birthday this year, and my mother is in her early 80’s); having lost my step-mom almost exactly a year ago; with my husband 25 years this November; and with both daughters mostly living on their own (one in her last year at McGill, and the other now in Seattle). Mortality and questions of what to do with the rest of my life loom large. And so, reading “The Dead” to my friend Bill, who is himself getting closer to 80, was a sobering and awesome experience. Of course there are the phenomenal notes of beautiful writing. Who can resist passages like this:

The morning was still dark. A dull yellow light brooded over the houses and the river; and the sky seemed to be descending. It was slushy underfoot; and only streaks and patches of snow lay on the roofs, on the parapets of the quay and on the area railings. The lamps were still burning redly in the murky air and, across the river, the palace of the Four Courts stood out menacingly against the heavy sky.

Or that impossibly exquisite last paragraph that almost demands to be read aloud:

A few light taps upon the pane made him turn to the window. It had begun to snow again. He watched sleepily the flakes, silver and dar, falling obliquely against the lamplight. The time had come for him to set out on his journey westward. Yes, the newspapers were right: snow as general all over Ireland. It was falling on every part of the dark central plain, on the treeless hills, falling softly on the Bog of Allen and, farther westward, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling, too, upon every part of the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

But as Bill and I discussed, the wonder of The Dead is that somehow, in 40 pages, Joyce manages to capture all of it: the absolute mundaneness of daily life, of almost inane small talk, of caricatures of people — friends, acquaintances, family — with whom we are all familiar; and then the move into the deepest parts of our consciousness (or unconscious?), those extraordinary moments where we look at someone we know exceedingly well, perhaps a spouse of many years, and see them anew, desire them anew, and feel a moment of intense connection, only to realize that what you are feeling in that moment is not being shared by them — that they are somewhere else entirely, in the memory of something (someone) that has nothing to do with you, but is just as intense. And that awareness of the privacy of our individual interior lives, the absolute depth of that privacy, is captured so resolutely in “The Dead.” And yes, (that yes again!), that yes is Joyce’s resounding answer to why we continue to go on, why we keep yearning and seeking and looking for connection in the face of the awareness of the coming winter of our lives that we inevitably cannot escape.

My appreciation of Joyce’s genius is very high right now. But it is not just the genius of his writing or the breadth of his knowledge about almost everything as exemplified by Ulysses (including Judaism, anti-Semitism, Hebrew, etc, which I surprisingly did not remember from my initial reading!) It is something else entirely: it is Joyce’s ability to capture human frailty through language, and at the same time, to depict the limitations of language to describe the greatest of human emotions like love, despair, grief. And yet, even with those limitations, he succeeds in leaving his readers astonished, feeling something that they know not how to put in words no matter how hard they try. So I will turn to Joyce again, a few sentences before that final paragraph of “The Dead”:

His soul had approached that region where dwell the vast hosts of the dead. He was conscious of, but could not apprehend, their wayward and flickering existence. His own identity was fading out into a grey impalpable world: the solid world itself which these dead had one time reared and lived in was dissolving and dwindling.

Those dead are still with us.